The umbilical cord—often called the baby’s lifeline—is one of the most remarkable structures in human development. Hidden from view for most of pregnancy, this flexible, rope-like organ connects a growing fetus to its mother, ensuring nourishment, oxygen, and life itself. Though it serves a temporary purpose, the umbilical cord plays a role so vital that without it, human life in the womb would be impossible.

Beyond basic biology, the umbilical cord carries fascinating scientific facts, clinical importance, cultural symbolism, and promising applications in regenerative medicine. This article explores the cord from formation to future medical use, written for learners and curious readers.

Anatomy and Structure of the Umbilical Cord

Basic Overview

The umbilical cord develops early in pregnancy, usually around the fifth week after conception. By the end of the first trimester it acquires its familiar rope-like appearance—typically about 50–60 cm (20–24 inches) long and about 2 cm thick.

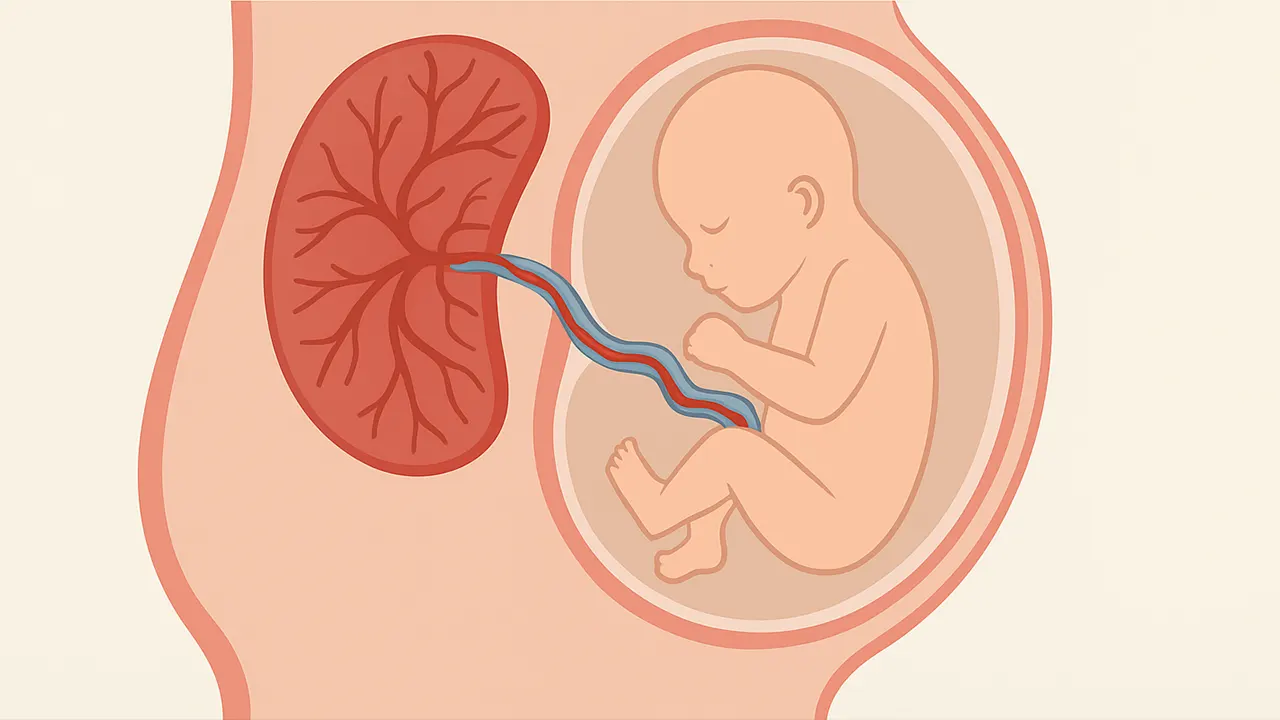

Simply put, the umbilical cord is the tubular connection between fetus and placenta, the organ that anchors the pregnancy to the uterine wall.

Components of the Umbilical Cord

- Two umbilical arteries — carry deoxygenated blood and fetal waste to the placenta.

- One umbilical vein — carries oxygen-rich blood and nutrients from the placenta to the fetus.

- Wharton’s jelly — gelatinous connective tissue that cushions and protects the vessels.

- Amniotic membrane — a thin covering that keeps the cord slippery and flexible.

Why the Cord Rarely Tangled

Fetal movement is vigorous, yet dangerous tangles are relatively uncommon. Reasons include:

- Wharton’s jelly makes the cord buoyant and resistant to kinks.

- Amniotic fluid allows the cord to float freely.

- High elasticity: the cord can stretch 30–40% without damage.

That said, true knots or significant compression can occur—roughly in 1% of pregnancies—and are monitored clinically.

How the Umbilical Cord Works

The Placenta Connection

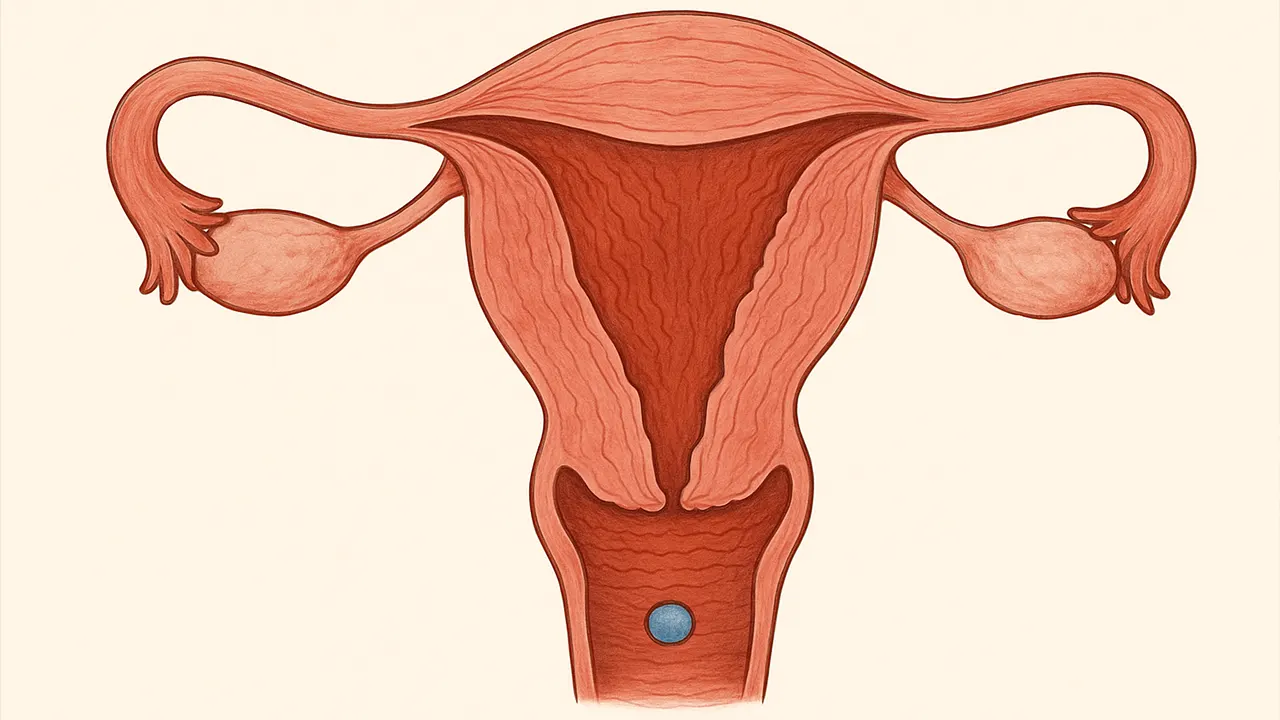

The placenta is a complex, temporary organ attached to the uterine wall. The umbilical cord links the fetus to the placenta so that:

- Oxygen and nutrients diffuse into fetal blood.

- Carbon dioxide and waste pass from fetal to maternal blood for disposal.

Importantly, the mother’s and baby’s blood do not directly mix; microscopic membranes separate the circulations while allowing essential molecules to pass.

Veins and Arteries: A Reversed Role

Unlike adult circulation, the umbilical vein supplies oxygenated blood to the fetus, while the arteries return deoxygenated blood to the placenta—a reversal that reflects the fetus’s reliance on maternal oxygenation.

Nutrient and Hormone Exchange

Through the cord, the fetus receives:

- Oxygen

- Glucose and amino acids for growth

- Fatty acids, vitamins, and minerals

- Maternal antibodies (passive immunity)

- Regulatory hormones that influence growth and metabolism

Developmental Journey of the Cord

Formation

Key milestones:

- ~Day 13 post-fertilization: primitive connection forms between embryo and yolk sac.

- Weeks 4–5: the early umbilical cord appears as the embryo and chorionic sac elongate.

- Weeks 6–12: physiological herniation occurs when the midgut temporarily enters the cord and returns by week 12.

Growth and Maturation

The cord grows with the fetus. Short cords (too short) can limit movement and complicate delivery; excessively long cords may loop or wrap (e.g., nuchal cords) but generally are tolerated well.

The Umbilical Cord After Birth

Cutting the Cord

After delivery, the cord is clamped and cut—a symbolic and biological rite of passage marking neonatal independence. Since the cord contains no nerves, clamping and cutting is painless.

Recent evidence favors delayed cord clamping (waiting 1–3 minutes or longer), which allows additional placental blood transfer, improving newborn iron stores and circulatory stability.

The Umbilical Stump

A small stump remains attached to the baby’s belly and typically dries and falls off within 7–14 days, leaving the navel (belly button). The final shape of the navel depends on how the skin heals, not how the cord was cut.

Medical and Scientific Importance

Cord Blood: A Source of Stem Cells

Umbilical cord blood contains hematopoietic stem cells, useful in treating:

- Leukemia and lymphoma

- Certain anemias

- Immune deficiencies

Parents can donate to public banks or store privately — both options have pros and cons.

Wharton’s Jelly and Mesenchymal Stem Cells

Wharton’s jelly contains mesenchymal stem cells that can differentiate into bone, cartilage, and muscle cells. This tissue is under research for potential applications in regenerative medicine.

Umbilical Catheterization

In neonatal intensive care, clinicians may insert catheters into umbilical vessels to deliver medications, nutrition, or to sample blood, providing critical access for newborn care.

Historical and Cultural Perspectives

The umbilical cord has carried deep meaning across cultures:

- Ancient Egypt: cords and placentas were sometimes preserved as sacred objects.

- Maori (New Zealand): burying the cord tied a child to ancestral land.

- Japan: the dried cord (heso no o) was kept as a keepsake.

- Many African and Native American cultures preserved cord fragments as talismans of protection.

The phrase “cutting the cord” has become a universal metaphor for gaining independence, and the umbilical connection is a frequent symbol of unity and origin in art and literature.

Complications Related to the Umbilical Cord

Nuchal Cord

When the cord wraps around the baby’s neck; found in up to 25–30% of births. Usually harmless, but monitored during labor.

True Knot

A real knot formed when the fetus moves through a loop of cord. Rare (~1%) but can tighten and restrict flow.

Cord Prolapse

When the cord descends into the birth canal ahead of the baby, it can be compressed—this is an emergency often requiring rapid delivery.

Single Umbilical Artery

Some cords have only one artery (instead of two). Occurs in ~1% of singletons and may be associated with other anomalies, though often the baby is healthy.

Velamentous Cord Insertion

When the cord attaches to fetal membranes rather than the placental mass; increases the risk of bleeding in delivery.

Ultrasound and Doppler imaging are essential tools to detect many of these conditions prenatally.

Modern Practices and Innovations

Delayed Cord Clamping

Waiting before clamping improves infant iron reserves and reduces anemia risk for months after birth.

Cord Milking

A technique which gently pushes blood through the cord toward the infant prior to clamping—used sometimes in preterm deliveries where immediate neonatal care is required.

Cord Blood Banking

Options include public donation or private storage. Private storage provides potential familial access but is relatively costly and the probability of use is low.

Artificial Cords and Research

Researchers study bioengineered cord models for fetal research and to advance artificial womb technology—a field that may impact care for extremely preterm infants.

Fascinating Facts About the Umbilical Cord

Umbilical Cord in Modern Medicine & Research

Regenerative Medicine

Cord-derived hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells are being researched for:

- Organ and tissue regeneration

- Spinal cord repair

- Diabetes therapies

- Neurodegenerative disease research

Ethical and Practical Considerations

Collection after birth avoids many ethical concerns tied to embryonic stem cells, making cord-derived cells a promising and ethically palatable research source.

Future Vision

Cord cells could enable personalized cellular therapies, tissue engineering, and even anti-aging research. What was once medical waste may become a cornerstone of future therapies.

Caring for the Umbilical Stump

New parents should follow simple care rules:

- Keep it dry — moisture delays healing.

- Fold diaper down — avoids rubbing and allows airflow.

- Avoid unnecessary antiseptics — water is usually sufficient.

- Don’t pull the stump — let it fall off naturally.

- Watch for infection — redness, swelling, foul odor, or pus require medical attention.

Umbilical Cords in Twins & Multiples

Twin pregnancies bring extra variety:

- Dichorionic twins have separate placentas and cords.

- Monochorionic twins share a placenta; unusual vascular connections can cause twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS), requiring monitoring and possible laser therapy.

Fun & Cultural Trivia

- Some families keep the dried stump in a keepsake box for sentimental reasons.

- In certain traditions, the cord is buried under a tree or in ancestral land.

- Burning the dried cord was once believed to ward off illness in some cultures.

- The phrase “umbilical cord of the internet” has been used metaphorically for undersea data cables.

Summary and Reflection

The umbilical cord is more than a temporary biological tube—it is the literal and symbolic lifeline between mother and child. Its role in transferring oxygen, nutrients, and immunity makes it a marvel of natural design. Beyond birth, cord blood and tissue are becoming powerful medical resources, while cultural practices emphasize the cord’s symbolic weight.

From formation through delivery and into the era of regenerative medicine, the umbilical cord remains a profound example of how small structures can hold great significance.

Key Takeaways

- The umbilical cord connects fetus and placenta and contains two arteries and one vein.

- Wharton’s jelly protects the vessels and the cord is highly elastic.

- Delayed cord clamping has measurable neonatal benefits.

- Cord blood and tissue are rich in stem cells and valuable for medicine.

- Cultural traditions around the cord highlight its symbolic power.